John Wilkins Subset

As the above epigram alludes to, quintessence in the Early Modern period referred to that mysterious fifth part of the cosmos hinted at in Aristotelean matter theory. For West and many others, what Aristotle left out of his elemental description of matter was meaning itself. That is why the work of natural philosopher and linguist John Wilkins was seen as an exploration of quintessence. From his early work on cryptography in Mercury to his magnum opus, An Essay towards a Real Character and a Philosophical Language, the most comprehensive attempt at a universal language in the seventeenth century, Wilkins sought to bring scientific order to this elusive fifth part of nature. Indicating at the same time essence and transformation, the metaphoric mutability of quintessence could serve as a catalyst both for Wilkins and also for the “metaphysical poet” par excellence, George Herbert. This concept of quintessence has undergirded our ongoing corpus exploration project – this website combines a number of different computational tools to describe both the more essential structures of language along with the simultaneous transformation of semantic meaning in the Early Modern period.

The unexpected conceptual relationship between John Wilkins and George Herbert helps to illustrate this quintessential doubleness. While both men were devout protestants (Wilkins became Bishop of Chester later in his life, and Herbert was a rector at St. Andrews’ Church in Salisbury) who wrote on religious topics, they are often positioned on opposite ends of the discursive spectrum. John Wilkins was the embodiment of the “plain speaking” rational man, a founding member of the Royal Society who aimed to discipline language through scientific empiricism. George Herbert, on the other hand, was second only to John Donne in his commitment to metaphysical ideals. As Herbert describes in The Sinner, “In so much dregs, the quintessence is small, / The spirit and good extract of my heart / Comes to about the many hundredth part,” (236). The quintessence that animates Wilkins’ linguistic experimentation appears, for Herbert, to be overtly spiritual.

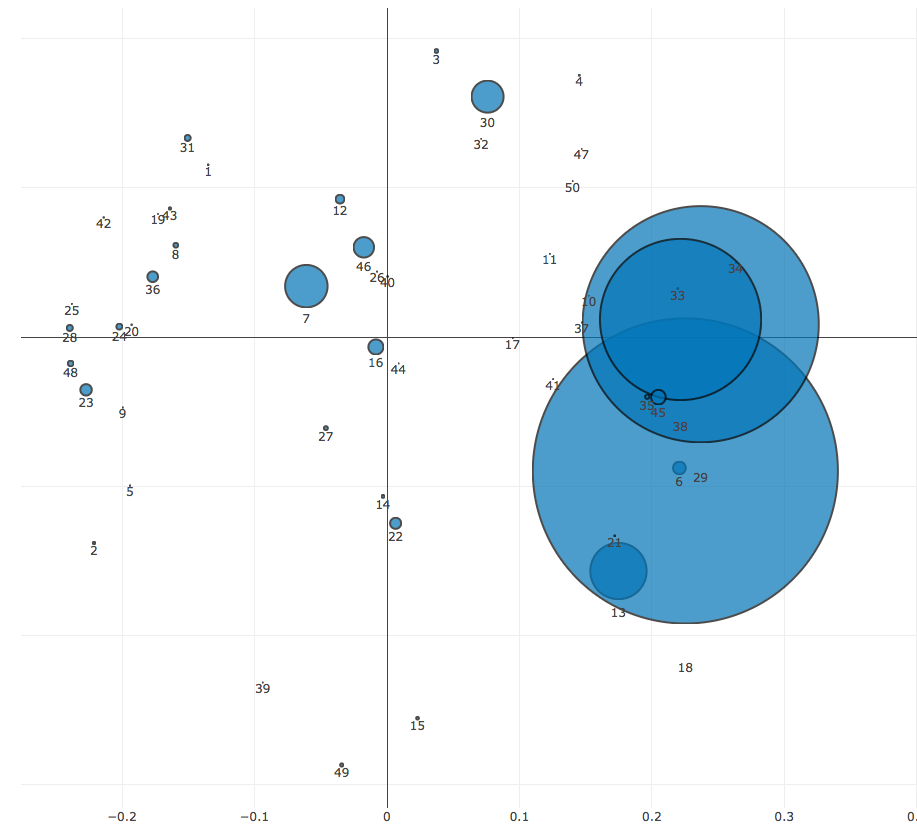

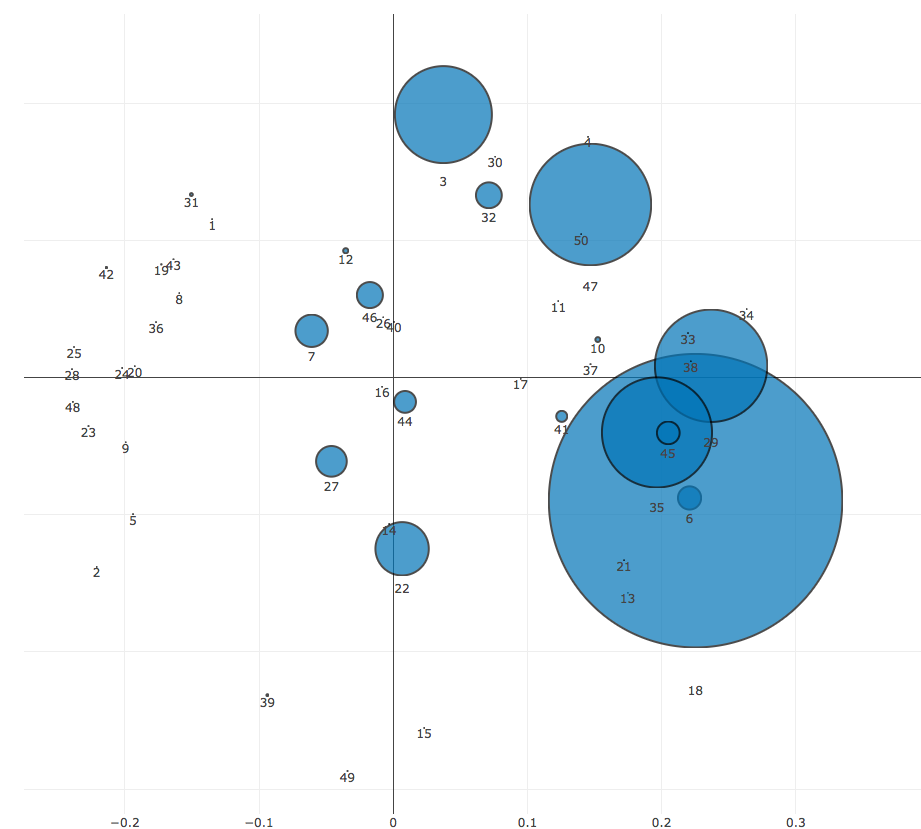

But if we use the tools in Project Quintessence to explore the broader contours of these two authors’ oeuvres, clear patterns emerge. In fact, by subsetting our full topic model to just these authors, we can map the similarity of their topics:

John Wilkins Subset

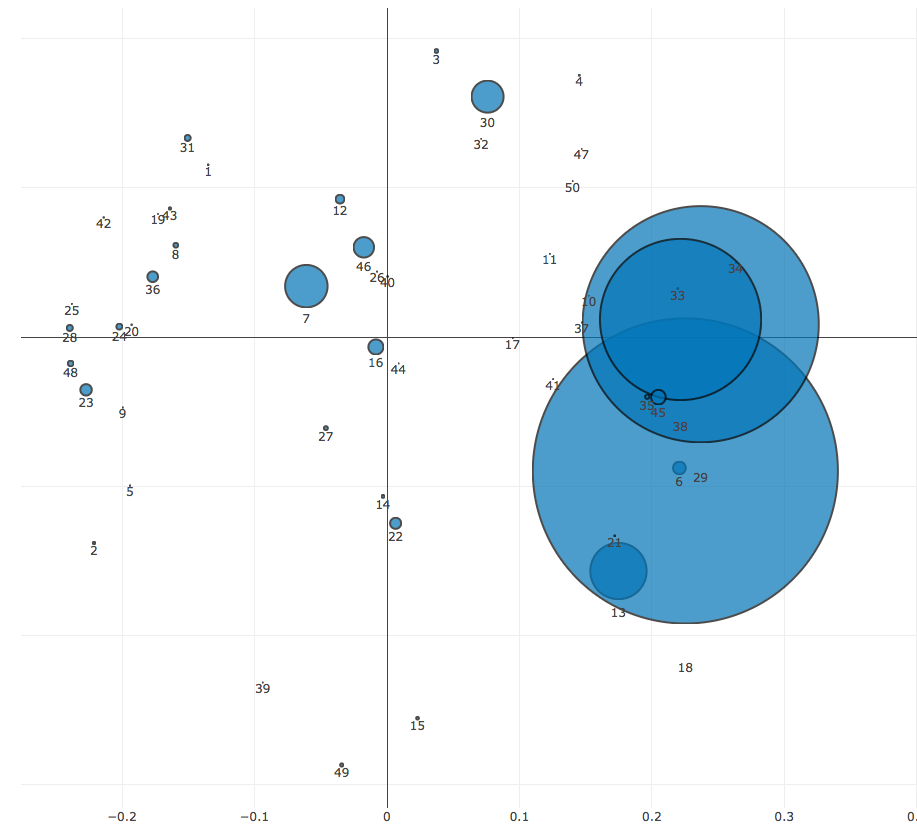

George Herbert Subset

While crucial differences remain, it is clear that these writers share a strong conceptual relationship – particularly in topics 18 and 29 -

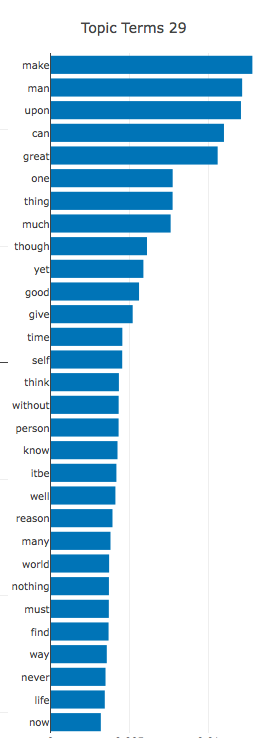

Topic 29

Topic 18 is clearly a religiously-inflected topic, which should not surprise us. Topic 29, on the other hand, is characterized by terms like “man,” “think,” reason,” “time” and “life.” And while Herbert’s texts are heavily represented by the existential Topic 35; “good,” “life,” “know,” “death,” and “live,” Wilkins engages a more naturalistic vocabulary with Topic 38; “make,” “thing,” “nature,” “body,” “reason,” “motion,” and “natural.” But the position of both texts in the lower right quadrant of our model is no accident – these topics are positioned according to their vocabulary similarity reduced to its principal components. In other words, the substantial overlap between the models for Herbert and Wilkins indicates a more profound similarity between the topics discussed by the two authors. Emphasizing both mind and body, man and nature, these topics combine both the essential and transformative qualities of quintessence. An examination of the change in the term quintessence over time helps to illuminate why these terms share an uneasy alliance in Topic 29:

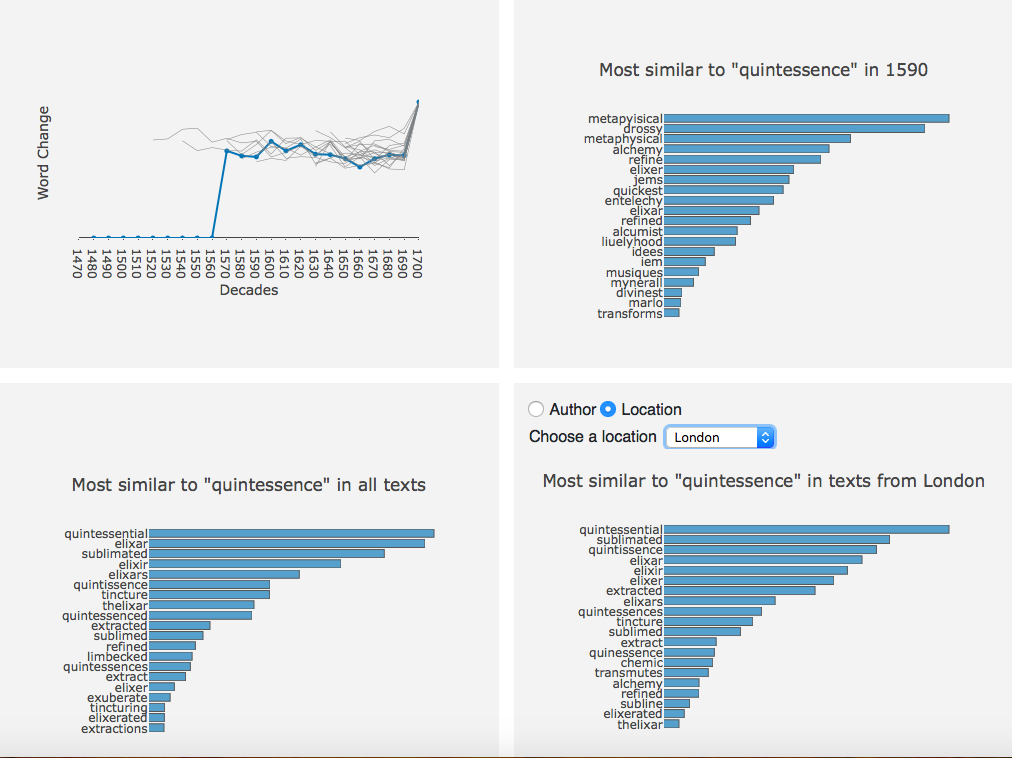

While quintessence bears a clear relationship with alchemy throughout its presence in the corpus, it changes the most between 1660 and 1700. Most closely associated with “metaphysical” in 1590, quintessence concludes its semantic shift in 1700 by bearing the closest similarity to “empirics.” The essence of English discourse itself appears to have undergone tremendous transformation in this period.

Of course, it is important to bear in mind the limitations of our project, both in scope (due to limitations with our digital archive) and in precision (the many behind-the-scenes decisions that have to be made in projects such as this). While this project can be used to answer questions never before tractable for Early Modern scholars, it is still limited in many ways. At the same time, we do our best to make these limitations and decisions transparent, to allow for this project to be referenced and relied upon by researchers. As you navigate around the site, look out for the help icons that display additional information about the tools you’re looking at and how they are built. Finally, any texts you are looking at that we have distributive access to can be downloaded for further analysis. Any good digital project must be paired with in depth historical and textual analysis.

Like quintessence in 16th and 17th century England, this project will continue to be transformed and refined over time. This is not simply a recovery project, but a search for essences that in themselves were in formation and transformation. The unbinding, transription, digitization, and reconstitution of Early Modern texts that form the basis of our archive present both new problems and new possibilities for research and anaylsis. Our goal is to open many new avenues of computationally-informed research into English textual analysis, and we will continue to sift through the archive in search of linguistic tinctures and elixirs that might, at last, discover this World’s fifth part.